14. The Spiral Path

Renouncement is an old idea. It comes from the monasteries, both East and West. The monks, nuns, sannyasins, and yogis all practice some forms of renouncement. While a few of us may want to choose such a life, most do not. There are communities in Cafh devoted to living the idea of renouncement, but the majority of members live lives just as everyone else. The Great Work for all is the same, though: how to live centered in the spirit of renouncement in the modern setting. What does that even mean? Is it possible? How is it connected to love? In some sense, what is practiced is “applied spirituality.” The focus is not on ideas or beliefs; it is on actual experience. The core of Cafh is the daily application of a clear, flexible method oriented towards living in a less and less self-centered way, and learning to see oneself as part of the bigger whole.

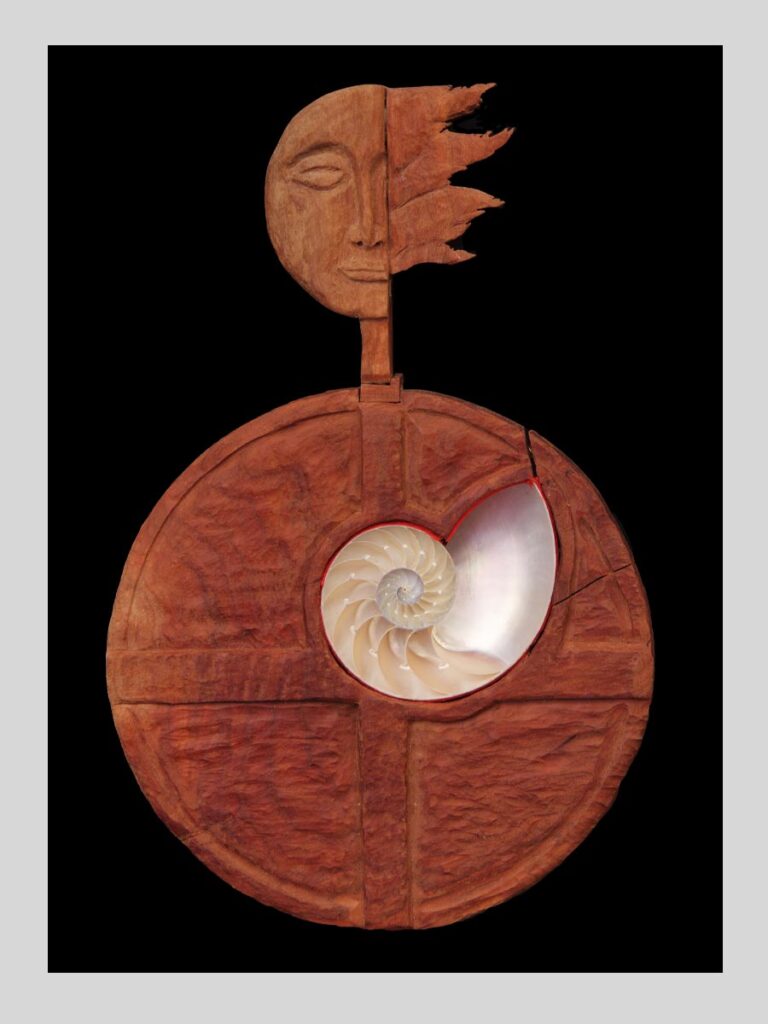

A story is told of the founder of Cafh, Don Santiago Bovisio: One day in the 1940’s when on a spiritual retreat in the countryside of Argentina, a student asked Santiago Bovisio to explain the difference between Cafh and other spiritual paths. Don Santiago drew a circle with his finger in the dust. “This circle is the ‘I’; everything outside its border is the totality of reality.” Then with his finger he erased the circle and said: “This is the way toward Union in some paths, such as Buddhism.” With his finger he drew another circle, and began to expand it as a spiral, wider and wider, saying: “This is the way toward Union in Cafh, expanding the ‘I’ by encompassing more and more of reality until we embrace the Infinite…”

Each person experiences Cafh in his or her own way, but there are clear teachings that underline the direction that is suggested. Thus, when I try to explain the path in understandable terms, it is my own idiosyncratic understanding. It comes, however with over 40 years of daily effort in conjunction with many meetings, retreats and teachings and work with others.

Cafh is path whose goal is love, though not necessarily in the way that word is most often used. Its method is to learn to be inclusive, a widening, ever more inclusive spiral whereby one tries to respect and appreciate the experience of others. With that effort comes a sense of participation in the world, a sense of union: the opposite of that sense of loneliness and alienation that is often found in modern life. It is not always easy, especially with others who are different or threatening. It takes imagination and daring to make the conscious, systematic attempt to learn empathy and to recognize that the self-centered, default point of view is just one point of view, sometimes necessary, but more often limiting.

The method of Cafh fosters “holistic thinking,” the profound realization that while we are each a whole, we are also parts of greater wholes—our family, community, nation, race, humanity, our planet, the universe. To use Ken Wilber’s term, we are “holons.” To let those facts sink into one’s habitual consciousness changes the context in which life happens. It is to see ourselves no longer as independent or dependent beings, but interdependent, woven together in a vast fabric of relationships. It is a world view, expansive and open-ended, centered in the eternal present but taking into account the vast, unimaginable time in which we participate.

While the past continually influences us, it is one thing to be its slave, endlessly repeating old habits, thoughts and feelings, and another to be fully in the present moment. Renouncing, letting go of the entrapment of the past while learning its lessons, is part of the meditative mind one works to cultivate. It could be called inner freedom.

We are quite aware of the freedoms others may try to take away from us, but more often than not we are unaware of how we have trapped ourselves in our own prejudices, reactions and ignorance. They are the taken-for-granted “truths” we become conscious of only now and then, when, for example, we enter another culture or meet someone with a vastly different world experience. To explore this prison we ourselves have built requires honesty and courage and the ability to look into uncomfortable parts of ourselves—to peer into our own shadows. In Cafh, we use meditation as a means to do this difficult work, but we do it under the guidance of the broadest, deepest, most loving power imaginable, the “Divine Mother,” whom we invoke.

A change in our frame of reference, the context in which we see people, events, and the natural world, alters the meaning we give everything. Through the meditation exercises, we learn to renounce our habitual way of “seeing” and to see with new eyes. We then practice applying these exercises to our own life. Seven basic, universal themes which facilitate spiritual unfolding are taught. Each has ancient, archetypal roots but is highly flexible, almost like a mathematical equation where one’s own life, experience and imagination fill in the variables.

A practical way to introduce renouncement is through the theme “The Two Roads.” Who has not felt attachment to habits, things, ideas and people which hold you back? As I use the meditation exercise to process these desires and fears that I am attached to, I learn to let go of them. In this way, the theme “The Two Roads” shows me that to renounce is to let go of one “road” or habit or way of being and to be open to another way. In the next theme, called “The Standard” one chooses what this new path is to be about.

Sometimes the meditation exercises are very general, and other times very specific. Each gives a somewhat different direction, for their purpose is to guide one in everyday life. Indeed, in the “big picture,” the point of the meditation exercises is not an experience limited to the time of the exercise, but part of the larger project of orienting one’s daily life in a more conscious, sacred direction. It is an open-ended process marked by real changes in thoughts, feelings and behavior. The goal is to expand one’s state of consciousness and learn to live with this expanded awareness.

For example, if I am a new parent, I am often shocked by how much time is needed to care for a new baby or young child. From the pre-parent, more or less self-centered frame of reference, where most of my efforts were determined by my goals (no matter how noble), this care-giving may feel like an onerous chore. However, when I love the child and see what he needs to grow well, it is not an onerous chore but that which just needs to be done. And I want to do it well. It is life. While I may see these efforts, in the initial frame of reference, primarily in terms of sacrifice, from the broader frame which accepts the responsibility of parenthood as primary, it is just what needs to be done. This change in perspective is the key point in how one views “renouncement.” From the self-centered point of view, it is a heroic sacrifice, but from the new reality of which I am now aware, it is just what needs to be done; I am just responding to the new awareness. To renounce is to choose what needs to be done from the most expanded state of awareness that I can “handle,” tempered by the practicalities of daily life.

We cannot avoid renouncement. It is a part of every decision we make. One could say that renouncement is simply a fact of life, and the real issue of spiritual life is discernment—What am I going to renounce? This discernment arises from my state of consciousness, the degree of awareness that I have, not only of the world outside of myself, but also my inner life. Self-knowledge and being honest with oneself, including about one’s own intentions, is the foundation of all of this. To be able to look deeply into one’s inner workings, to see how they affect one’s perceptions, and to see the way one’s feelings affect the way one relates to the world is not easy. We have all had these moments of awareness. Can we make this awareness the guiding light in our lives?