16. Deep Questions: An Interview With Piet Hut

When we ask deep questions, at first it seems that the answers can be found by digging, by extending our usual explorations to greater depth. However, when we persist, we always find something totally unexpected, and qualitatively different. And then we realize that the “totally other” forms the basis for the world we thought we knew. This is the greatest surprise. And in this way, we realize that our everyday view of the world and of ourselves was never more than a summary picture, convenient for getting around in our daily life, but only a story, worse than inaccurate, in fact totally wrong in its essence.

When we asked about the structure of the Universe, it became clear, first, that neither the Earth nor the Sun are in the center of the Universe. For a few hundred years our understanding of our Universe offered a picture that grew ever vaster in space and time. But then we began to understand that our Universe had originated in a Big Bang, in the tiniest of beginnings, possibly at the origin of time itself. We can now trace the initial footprint of our own galaxy back to a space smaller than that of an atom.

Piet Hut, “Snippet” from the Ways of Knowing website

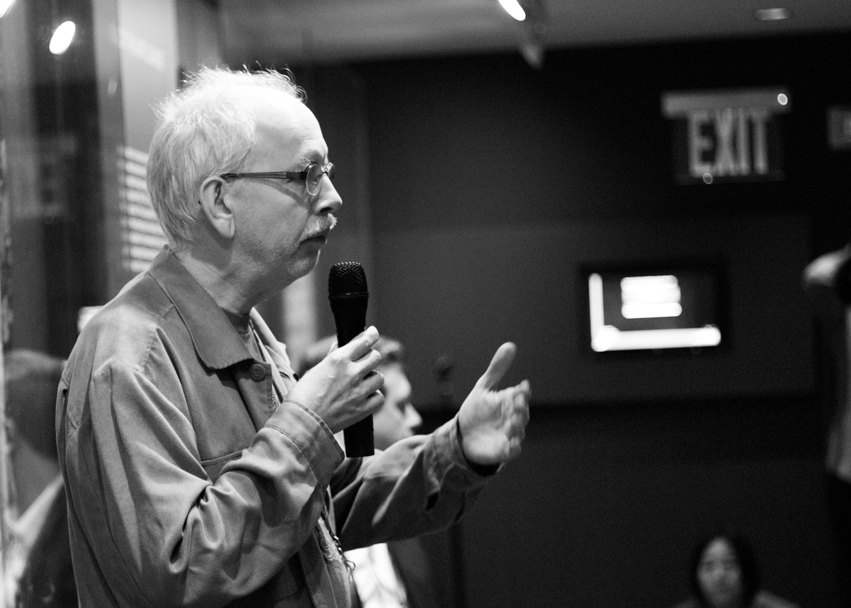

Piet Hut is an astrophysicist and Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University, an institute whose members have included such luminaries as Albert Einstein, Robert Oppenheimer, Kurt Gödel and Freeman Dyson. His interest is to bring the same rigor that has been brought to the objective world, the material world of space, time and energy, to the subjective world, that world in which spirituality and religion flourish. Piet has been a participant in the Dalai Lama’s Science and Life seminars and appears in the Dalai Lama’s recent book The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality (Morgan Road Books, 2005).

One way to formulate his approach is to say that both science and the experiential cores of various religions are different ways of knowing, covering different aspects of the same reality. Both are growing in time, and their terrains of applicability are likely to overlap more and more. What currently may look like complementary approaches to understanding the world may, in due time, converge into a single body of knowledge. For the time being, however, a dialogue between science and spirituality should focus on what Piet calls “roots, not fruits,” a comparison of the experimental methods of investigation, rather than the resulting theories which often take the form of dogmas, both in science and religion.

Such an investigation of roots inevitably brings one to the religious mystics and to scientific geniuses. Piet is particularly interested in looking at and working with contemplative traditions with the goal of finding what is common and less culture-specific in each. This involves not only an arms-length study of these traditions, but an actual engagement with their practices, seeking insights into the way that reality may be perceived by such methods. At the heart of religions are such insights, but they are often veiled in culture-specific images and metaphors. Rather than dismissing such insights as stories and legends, he seeks to understand the experience out of which these truths arose. It is easy to see that Piet’s approach has the possibility of offending both the scientists, committed (mostly tacitly) to a materialist paradigm, where consciousness and all that is subjective are simply a side effect of brain-cell functioning, and the religious, who think that the authority of their religion, whether it resides in a book or a leader, is unquestionable. Remarkably, the Dalai Lama, one such leader, has made a widely quoted statement that “if scientific analysis were conclusively to demonstrate certain claims in Buddhism to be false, then we must accept the findings of science and abandon those claims.” It would seem to this writer that this openness has its exact parallel in Cafh, my own spiritual path, and I am hopeful we can explore this road in this interview.

SEEDS: I would like to begin by asking how it is that you have chosen to be involved with such diverse areas as astrophysics, contemplative traditions and consciousness studies. The path you have walked seems unusual inasmuch as most scientists I have known seem to get more and more specialized and become less and less seriously interested in areas outside their specialty as time goes on.

PIET: For me personally, what connects them—to say it in a simple way—is that I am interested in the structure of reality. If I had been able to go to university at age 18 and if there had been a department of “reality studies,” I would definitely have gotten my degrees there. Because there wasn’t, I had to choose either astrophysics or philosophy or anthropology or language studies. (Language, of course, also determines our view of reality very much, too.) I decided to study our view of the material universe on the largest scale, astrophysics, but at the same time, I kept a strong interest in other areas. Specifically I have found that what for me connects philosophy and spirituality on the one hand, and science on the other, is the laboratory method. It is the notion that you can actually test things and investigate things. That is really the thread that connects everything for me.

SEEDS: So you would see meditation or contemplation as a form of investigation?

PIET: Yes, absolutely. In most texts of mystics or contemplatives, they warn you that while you should start by trusting the tradition, at the same time you should not have too strong a view of what that particular tradition is like. You should make sure that whatever you believe, whatever conceptual belief you have, you can toss it away and make yourself open and available to direct experience. So it is important to believe something in order to get started, but it is also important to disbelieve or to doubt or to put your belief on the side. I think the same can be said for both science and spirituality.

SEEDS: You mentioned laboratory studies. Would you compare and perhaps contrast laboratory studies in astrophysics and in contemplation?

PIET: To start with, in astrophysics, strictly speaking, we don’t have a laboratory. We cannot put a star in a lab and do experiments on it. We can only look at stars from far away. The experiments are being done out in space, and we are guest observers, so to speak, with our telescopes. That was definitely true until about 50 years ago, when computers were invented. Now we can use computers to build a virtual laboratory where we can make simulations of stars and star clusters and galaxies.

As far as the connection with contemplative methods or spiritual practice goes, we can view our own life as a laboratory, which I find a very interesting metaphor to use. Each day that we live, all kinds of things happen, and we enter into the laboratory of every new day with all kinds of preconceived notions that we are testing out. Some of them seem to hold up well, while others don’t seem to hold up well. We learn something every day, and the whole idea of connecting your spiritual or meditative or contemplative practice with daily life is for me central. If you just go and sit and meditate to get some peace of mind, that is all good and fine as a form of therapy, but there are many types of therapy. Unless it really feeds back into your daily life and unless it really transforms the way you live and deal with yourself and with other people, I think it has only limited meaning.

SEEDS: Your description makes me think that discovery is a central aspect of both science and the spiritual path.

PIET: Yes, what is especially interesting are the similarities in the methods. The applications are different but the methods are similar. This connects to what I have sometimes called “roots not fruits.” The fruits are very different but the roots are surprisingly similar. What I am especially exploring is the role of the working hypothesis.

In science, you don’t start off by saying that you believe something or you don’t believe it, but you put forward a working hypothesis. You say, “Well, maybe it is like this. Maybe the earth is going around the sun or maybe the sun is going around the earth. These are two different hypotheses. Let’s explore them, let’s work with them. (That is why we say a working hypothesis.) Let us see what the consequences are.”

In spirituality, too, you can take a working hypothesis and apply it in your life and then see what happens with it. To take a very simple example, you can take as a working hypothesis that if someone is nasty to you, the best approach might still be to be nice and friendly to them. You can try it out and see what the consequences are. Rather than taking that as a direct command or fixed rule from God or your religious organization, you can take it as something to explore. I think that most of the so-called commandments of traditional religions probably originated in that spirit. They were given as a way to enrich your life and make it more balanced. Any rigid rule, if you follow it to the letter, can lead to all kinds of mistaken applications. It is generally the living spirit rather than the letter of the law that can really help you to live a good life.

SEEDS: Your response makes me see religion in a somewhat different light, as a repository of empirical knowledge about reality which arose from some original experiences. Perhaps the contemplative approach is to uncover and apply the methods that led to those original insights. It reminds me of the approach that has unfolded in physics of discovering simpler, more basic phenomena, laws and understandings out of which more complex phenomena can be understood. What do you think about this?

PIET: There is definitely a lot of empirical knowledge buried in most religions and connected with the religious tradition. Of course, the word religion is a complex notion. There are religions that were founded by a particular person, and there are also religions like Taoism and various nature religions in which you cannot point to one particular beginning. Even the religions which have a particular founder, if you look at the way they are being practiced nowadays, much of their content was added by later saints or venerated practitioners who believed they were following the founder, but who, themselves, injected all kinds of new angles. The word religion is rather complicated because it is a western concept which has been mainly used for describing Christianity and looking at other religions from a Christian point of view. It is doubtful if Buddhism can even be called a religion. It is certainly an attempt to describe cognition in a very broad sense, and includes psychology, philosophy and, indeed, religious practice.

So to compare science and religion these days is a rather tricky thing. Science is relatively young and rather well defined. It is very clear what physics is, what chemistry is, what biology is, what the rules of the game are, how you get a degree, how you get training. The whole thing is only a few hundred years old and its history has been very well recorded and preserved. In contrast, religions come in so many different forms. The roots are often completely lost in history and if you go to a conference on science and religion, sometimes it is a conference where Christian theologians talk to a few scientists, sometimes it is a conference that individuals from non-European religions attend as well, and sometimes it is a more philosophical discussion of science. What I am personally most interested in is to talk to those people in the religious traditions who are directly focusing on their own experience. They could be monks or contemplatives in Christianity or Buddhism or people practicing any type of religion. If these people can directly talk from their own experience, that would be most valuable and would provide the most balanced connection with science.

SEEDS: I note that you yourself have been exploring in this way and have attended some meetings on science and spirituality with the Dalai Lama. Could you share a little of what you have discovered in this process?

PIET: Most of what I have been doing for the last 35 years has been to try to get a working knowledge of both fields myself. In the process of learning more and more about contemplation, I have gone to different meditation centers, followed various workshops and retreats, and talked to a number of people from different traditions in Zen Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism, and in Christianity too. What I am now planning to do is to talk more specifically to some of those people with the intention of comparing their understanding with that of science. I haven’t really done much of that so far, because I have been too busy getting a basic background myself.

Now I feel well enough grounded in both science and spirituality to have at least a sense of the landscape and a taste of what both of them really are in a day-to-day practice. Now I want to spend the rest of my life helping to form a community of people who share this interest and work together with the specific aim of facilitating a modern way of engaging in these ancient practices, a modern way of probing into the structure of reality that will really have consequences for our daily life.

SEEDS: Does this modern way include using the Internet?

PIET: Definitely! The Internet is a wonderful way to find people in the first place. You put something on the web and then, sooner or later, someone approaches you saying, “That is interesting, that is very similar to questions I have.” I have met quite a number of interesting individuals who, out of the blue, wrote me about things that I had been putting up on the web. So that is one function: to connect people. Once they are connected, another function of a joint website is to have people communicate further and, in effect, form virtual retreats. They practice, each in their own place, but through the Internet they can exchange information.

This is exactly what Steven Tainer and I are doing on the Ways of Knowing website, which we started a year ago. It is going quite well. We now have a number of people involved who spend some time every day working with our approach. Once a week they write a summary and put it up on the web, and we comment on each others’ summaries. Learn about the current state of this project here.

SEEDS: Thank you very much for your time. I expect that some of the readers of Seeds of Unfolding will be interested in going to view and perhaps participate in this virtual community (www.waysofknowing.net), and I would hope that some of the readers of Ways of Knowing will find their way to the Cafh website (www.cafh.org).